| The week of December 7 is a week in which every Japanese-American has to face the legacy of history. I will admit, with much shame, that as a knucklehead adolescent I tended to make fun of Pearl Harbor Day, oftentimes threatening to go down to Cricket Hill and bomb the Eskimo totem pole. As I got older I started to realize that this was no joking matter, especially when I became a professional musician. One December 7 found me playing a cocktail reception at the military installation at O’Hare, in a room decorated with photos of the U.S.S. Arizona, and another December 7 found me playing a community theater performance out in Elgin; I was in the washroom, in a stall, and overheard two old guys at the urinals asking each other where they were “on that day”; one of them had been at Pearl. I stayed in the stall until they left. And I once dated a woman, a Southern belle, who warned me that her father was never to know about our relationship, because he had survived Pearl Harbor. People died, and people remember.

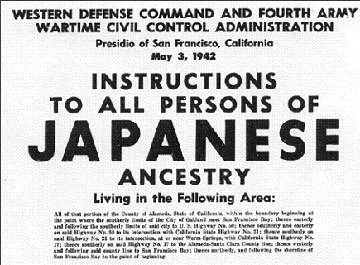

Of course, that cuts both ways. One of my best friends’ family has roots in Hiroshima, and I can only imagine what his feelings are every August 6. Throughout most of my life I’ve been aware that there’s a disconnect between what we were taught in history classes at school and what my family related to me. Ever since I was little I knew that my whole family had spent most of World War II “in the camps,” and that the adult men in the family had also served in the United States Army overseas. It wasn’t until I became a hippie that the inherent weirdness of that started to sink in. And even at this late date in history I continue to run into friends who have no idea what “the camps” were, or about the history of the Nisei in World War II was. I’ll try to be brief; in 1942 president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order |

Go For Broke Most of them were placed in two special units, the 442nd Combat Regiment and the 100th Battalion. Eventually the two units were consolidated, and included a Field Artillery battalion. The 442nd/100th served in the European theater; very few Japanese soldiers fought in the Pacific, although some served in intelligence positions, as interpreters. The 442nd/100th were the most-decorated units in the war, with amongst the highest casualty rates as  Uncle Mark well. My Uncle Mark was in the 442nd; my dad was not, although he did serve in Italy. I never got the story of why he didn’t go with the 442nd; he was younger than Mark, which might explain it (he was a company bugler). The 442nd’s motto was “Go For Broke,” which was also the title of a movie starring Van Johnson, about the unit. That movie is part of every Japanese-American of my age’s upbringing; I’ve probably seen it dozens of times, and most of my friends own copies of it, as do I. |

| The most famous legend of the 442nd’s history is the story of the Lost Battalion. Units of the 141st Regiment were cut off and surrounded by Germans in the Vosges mountains; suffering great casualties, the 442nd rescued them. The 442nd’s K Company suffered 386 casualties out of their 400 men.

So, I realize that I’m not responsible for Pearl Harbor, just as I realize you’re not responsible for Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But I feel justifiable pride in what the guys in the 442nd/100th accomplished, and I do wish that it was a better-known aspect of World War II history, as I also wish the Relocation Centers were too. And ever year on December 7 I’ll dwell on these thoughts. Steve Hashimoto This post appeared a couple years back in News From The Trenches, a weekly newsletter of commentary from the viewpoint of a working musician published by Chicago bassist Steve Hashimoto. If you’d like to start receiving it, just let him know by emailing him at steven.hashimoto@sbcglobal.net

Steve Hashimoto |

9066, which commanded all United States residents of Japanese ancestry to report to “relocation centers,” which were in essence concentration camps. The camps were located in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. By all accounts life in the camps was no picnic; I remember my mom and aunts talking about the sand blowing in through cracks in the walls and covering everything while they slept (snow, in the winter). You were only allowed to bring what you could physically carry, or lash to your vehicles, so almost everyone lost their homes, their farms, their businesses, their land, and most of their possessions unless they were lucky enough to have neighbors who’d watch over their interests (most did not; this resulted in what was essentially a land-grab by the Anglo Californians). And although many of the Japanese-Americans were understandably bitter and dispirited, the majority of them remained determined to prove that they were good American citizens. In this spirit thousands of young men volunteered to serve in the Army.

9066, which commanded all United States residents of Japanese ancestry to report to “relocation centers,” which were in essence concentration camps. The camps were located in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. By all accounts life in the camps was no picnic; I remember my mom and aunts talking about the sand blowing in through cracks in the walls and covering everything while they slept (snow, in the winter). You were only allowed to bring what you could physically carry, or lash to your vehicles, so almost everyone lost their homes, their farms, their businesses, their land, and most of their possessions unless they were lucky enough to have neighbors who’d watch over their interests (most did not; this resulted in what was essentially a land-grab by the Anglo Californians). And although many of the Japanese-Americans were understandably bitter and dispirited, the majority of them remained determined to prove that they were good American citizens. In this spirit thousands of young men volunteered to serve in the Army.

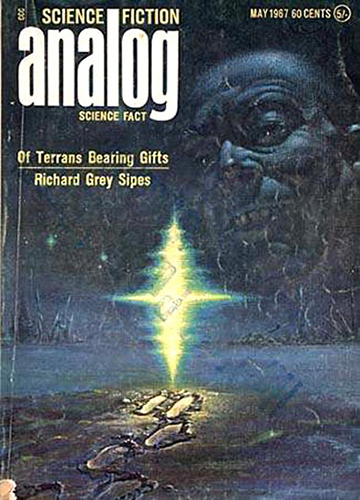

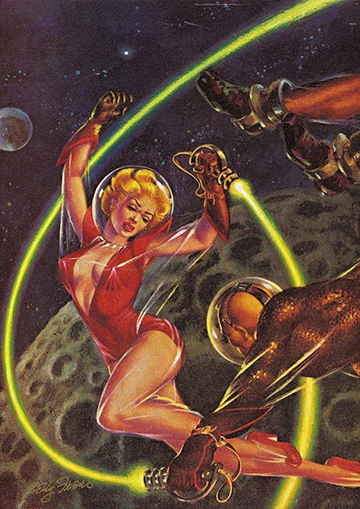

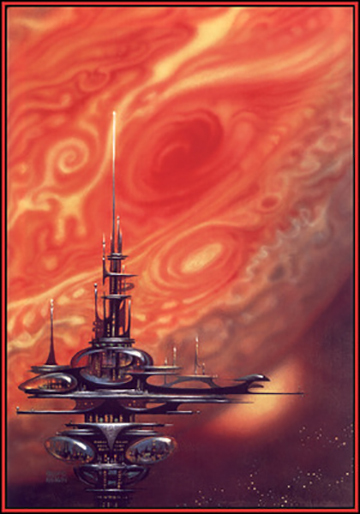

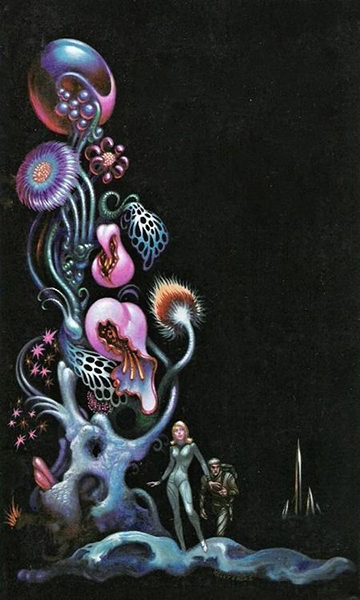

become aware of Freas’ work until I saw his cover for Analog Magazine in May of 1967. I had been a science-fiction reader (hardcore fans almost NEVER call it “sci-fi”) since I was very young; I think Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle In Time was my first, checked out from my grammar school’s reading room in 1962, followed by *Andre Norton’s Daybreak 2250 A.D.,* purchased from a mail-order book club. I wasn’t into the magazines so much, but some thing about Freas’ cover painting compelled me to buy this one; I have no memory whatsoever of the story that it illustrated.

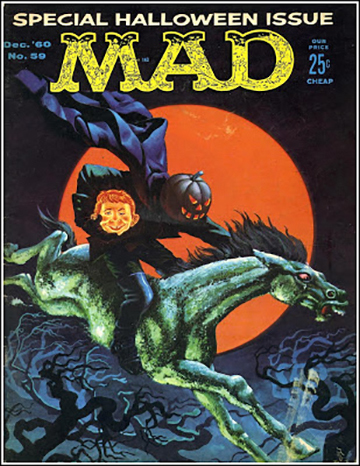

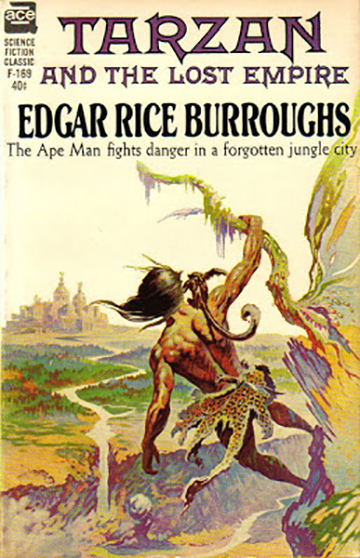

become aware of Freas’ work until I saw his cover for Analog Magazine in May of 1967. I had been a science-fiction reader (hardcore fans almost NEVER call it “sci-fi”) since I was very young; I think Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle In Time was my first, checked out from my grammar school’s reading room in 1962, followed by *Andre Norton’s Daybreak 2250 A.D.,* purchased from a mail-order book club. I wasn’t into the magazines so much, but some thing about Freas’ cover painting compelled me to buy this one; I have no memory whatsoever of the story that it illustrated. three book covers in 1952, and he started working for Astounding Science Fiction magazine in 1953; Astounding changed its name to Analog and Freas worked for them until 2003. He started working for Mad in 1957, and painted most of their covers until 1962, which would have been right around the time that I started reading the magazine. He also painted hundreds of covers for the paperback publishers Ace, DAW, Signet, Avon, Ballantine and Lancer.

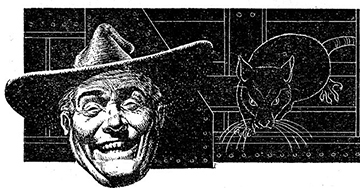

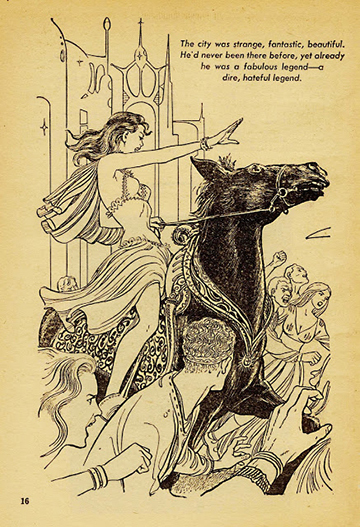

three book covers in 1952, and he started working for Astounding Science Fiction magazine in 1953; Astounding changed its name to Analog and Freas worked for them until 2003. He started working for Mad in 1957, and painted most of their covers until 1962, which would have been right around the time that I started reading the magazine. He also painted hundreds of covers for the paperback publishers Ace, DAW, Signet, Avon, Ballantine and Lancer. loved, pen and ink on a textured illustration board that used to be called either Ross board or coquille board; sports cartoonists used to use the technique a lot. After the

loved, pen and ink on a textured illustration board that used to be called either Ross board or coquille board; sports cartoonists used to use the technique a lot. After the

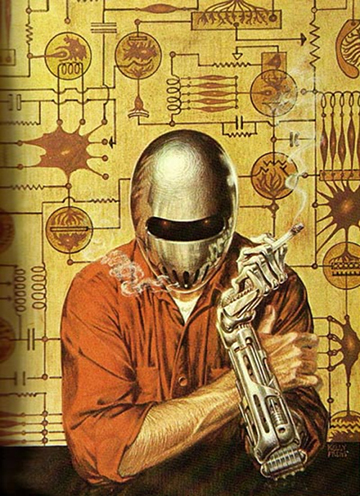

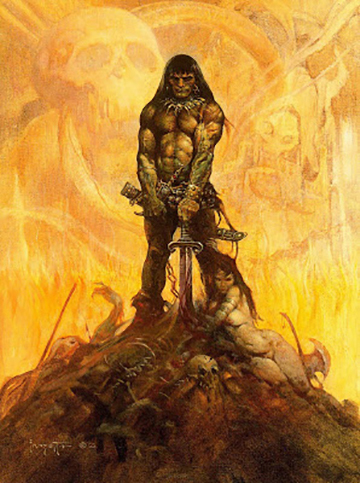

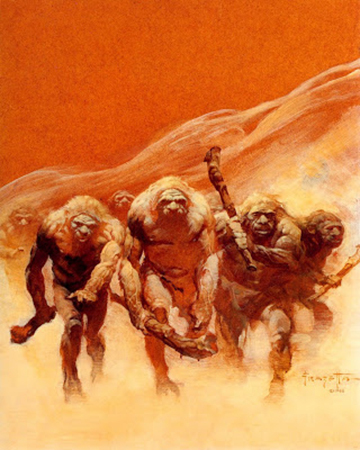

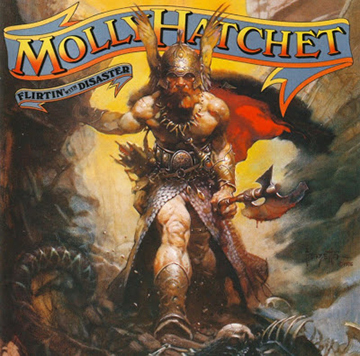

This week’s General Fave is the artist Frank Frazetta. I was going to describe him as “the fantasy artist,” but that’s only what he was best-known for; he also worked in the comics field, advertising, commercial illustration, and science fiction. He was part of the legendary EC Comics stable, and of what was known as the Fleagles, a loose-knit crew of young artists who evolved out of the EC stable to work on Mad Magazine. He drew what’s known in the comics world as ”funny animal” stories, as well as westerns, romance and science-fiction (one of his covers for the Buck Rogers comic book is iconic, much as I hate to use that word, but it applies); he was Al Capp’s assistant for 9 years, drawing mostly the sexy women in the Lil’ Abner comic strip. He also occasionally assisted on the Playboy comic feature Little Annie Fanny, mostly drawing Annie (Frazetta’s women were scandalously sexy; he always claimed that his wife Ellie was his principal model).

This week’s General Fave is the artist Frank Frazetta. I was going to describe him as “the fantasy artist,” but that’s only what he was best-known for; he also worked in the comics field, advertising, commercial illustration, and science fiction. He was part of the legendary EC Comics stable, and of what was known as the Fleagles, a loose-knit crew of young artists who evolved out of the EC stable to work on Mad Magazine. He drew what’s known in the comics world as ”funny animal” stories, as well as westerns, romance and science-fiction (one of his covers for the Buck Rogers comic book is iconic, much as I hate to use that word, but it applies); he was Al Capp’s assistant for 9 years, drawing mostly the sexy women in the Lil’ Abner comic strip. He also occasionally assisted on the Playboy comic feature Little Annie Fanny, mostly drawing Annie (Frazetta’s women were scandalously sexy; he always claimed that his wife Ellie was his principal model).

The work that catapulted him to pop-culture fame and recognition was probably the paperback cover work he did in the 60’s and 70’s, for Ace books’ Edgar Rice Burroughs editions (Tarzan, John Carter, etc.) and the Lancer books Conan series.

The work that catapulted him to pop-culture fame and recognition was probably the paperback cover work he did in the 60’s and 70’s, for Ace books’ Edgar Rice Burroughs editions (Tarzan, John Carter, etc.) and the Lancer books Conan series.

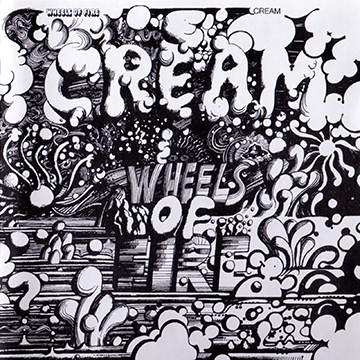

This week’s pick is more goddam hippie music; it’s the song “Deserted Cities of the Heart”, performed by Cream, written by Jack Bruce and Pete Brown, from the band’s 1968 album Wheels Of Fire. The basic band of Bruce, Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker were augmented on the studio disc (it was a double album, one disc recorded in the studio and the other live) by producer/multi-instrumentalist Felix Pappalardi. On this particular song Bruce plays bass, acoustic guitar, cello and sings; Clapton plays electric guitar; Baker plays drums and tambourine; and Pappalardi plays the viola.

This week’s pick is more goddam hippie music; it’s the song “Deserted Cities of the Heart”, performed by Cream, written by Jack Bruce and Pete Brown, from the band’s 1968 album Wheels Of Fire. The basic band of Bruce, Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker were augmented on the studio disc (it was a double album, one disc recorded in the studio and the other live) by producer/multi-instrumentalist Felix Pappalardi. On this particular song Bruce plays bass, acoustic guitar, cello and sings; Clapton plays electric guitar; Baker plays drums and tambourine; and Pappalardi plays the viola.

This week’s pick is by Herbie Hancock, from his 1969 album Fat Albert Rotunda. It’s the lovely (and difficult tune) “Tell Me A Bedtime Story.” Herbie’s on electric piano, with Joe Henderson on tenor sax and alto flute; Garnett Brown on trombone; Johnny Coles on trumpet and flugelhorn; Buster Williams on bass; Albert “Tootie” Heath on drums and George Devens on percussion. Herbie wrote the tune, and Rudy Van Gelder was the engineer.

This week’s pick is by Herbie Hancock, from his 1969 album Fat Albert Rotunda. It’s the lovely (and difficult tune) “Tell Me A Bedtime Story.” Herbie’s on electric piano, with Joe Henderson on tenor sax and alto flute; Garnett Brown on trombone; Johnny Coles on trumpet and flugelhorn; Buster Williams on bass; Albert “Tootie” Heath on drums and George Devens on percussion. Herbie wrote the tune, and Rudy Van Gelder was the engineer. This week’s pick is some country music, goddammit. It’s the gorgeous song “The Road To Ensenada” by Lyle Lovett, from the 1996 album of the same name. I couldn’t find a YouTube video of the album cut, so I don’t really know who those cats are, but they’re playing it really close to the recorded version; the players on the record are Lyle on guitar and vocals, and what’s essentially James Taylor’s studio band of the 90’s — Leland Sklar on bass, Russ Kunkel on drums and shaker, Dean Parks on electric guitar, Luis Conte on percussion and Arnold McCuller, Valerie Carter*8 and Kate Markowitz on background vocals, with ringers Matt Rollings on piano and Don Potter on acoustic guitar.

This week’s pick is some country music, goddammit. It’s the gorgeous song “The Road To Ensenada” by Lyle Lovett, from the 1996 album of the same name. I couldn’t find a YouTube video of the album cut, so I don’t really know who those cats are, but they’re playing it really close to the recorded version; the players on the record are Lyle on guitar and vocals, and what’s essentially James Taylor’s studio band of the 90’s — Leland Sklar on bass, Russ Kunkel on drums and shaker, Dean Parks on electric guitar, Luis Conte on percussion and Arnold McCuller, Valerie Carter*8 and Kate Markowitz on background vocals, with ringers Matt Rollings on piano and Don Potter on acoustic guitar.

This week’s pick is Stevie Wonder’s “I Wish.”It was released as a single in 1976, and then included on the album Songs In The Key Of Life in the same year. The musicians are Nathan Watts, bass; Hank Redd, alto saxophone; Raymond Maldonado and Steve Madaio, trumpet; Trevor Laurence, tenor saxophone; trumpet; and Stevie on vocals, Fender Rhodes, ARP 2600 Synthesizer, and drums.

This week’s pick is Stevie Wonder’s “I Wish.”It was released as a single in 1976, and then included on the album Songs In The Key Of Life in the same year. The musicians are Nathan Watts, bass; Hank Redd, alto saxophone; Raymond Maldonado and Steve Madaio, trumpet; Trevor Laurence, tenor saxophone; trumpet; and Stevie on vocals, Fender Rhodes, ARP 2600 Synthesizer, and drums.

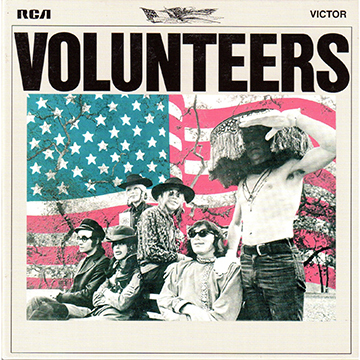

This week’s pick is hippie rock – Jefferson Airplane’s “Volunteers”. It’s from their 1969 album of the same name, and features what I (and I’d wager most people) think of as the “classic” lineup: Grace Slick and Marty Balin on vocals, Paul Kantner on guitar and vocals, Jorma Kaukonen on guitar, Jack Casady on bass, and Spencer Dryden on drums. Pianist Nicky Hopkins guests on this, and other, cuts. The song was written by Balin and Kantner.

This week’s pick is hippie rock – Jefferson Airplane’s “Volunteers”. It’s from their 1969 album of the same name, and features what I (and I’d wager most people) think of as the “classic” lineup: Grace Slick and Marty Balin on vocals, Paul Kantner on guitar and vocals, Jorma Kaukonen on guitar, Jack Casady on bass, and Spencer Dryden on drums. Pianist Nicky Hopkins guests on this, and other, cuts. The song was written by Balin and Kantner.

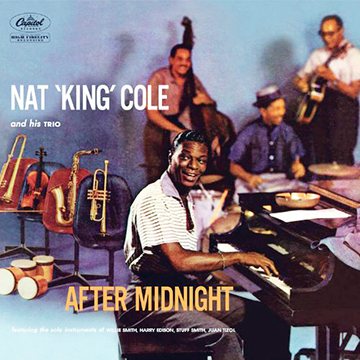

This week’s pick is the jazz standard ”Just You, Just Me,” from Nat “King” Cole’s After Midnight album. The song is by Jesse Greer and Raymond Klages, from a 1929 movie called Marianne. Cole’s album featured his trio, with Cole singing and playing piano, guitarist John Collins and bassist Charlie Harris. On this song, they’re joined by Lee Young, Lester’s brother, on drums, and Willie Smith on alto saxophone.

This week’s pick is the jazz standard ”Just You, Just Me,” from Nat “King” Cole’s After Midnight album. The song is by Jesse Greer and Raymond Klages, from a 1929 movie called Marianne. Cole’s album featured his trio, with Cole singing and playing piano, guitarist John Collins and bassist Charlie Harris. On this song, they’re joined by Lee Young, Lester’s brother, on drums, and Willie Smith on alto saxophone.