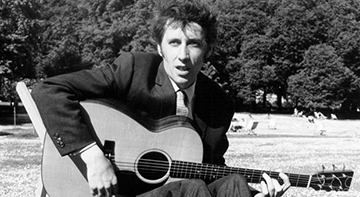

Bert Jansch

My old pal David Ashcraft gave me another great book by Colin Harper, the author of the John McLaughlin biography Bathed In Lightning. This one is pretty far afield from the McLaughlin bio but it turns out to be surprisingly of a piece; it’s a bio of the seminal English folk musician Bert Jansch, titled Dazzling Stranger: Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival.

Jansch is one of my favorite musicians, the leader of the band Pentangle, and although I never considered him much of a blues player, he certainly was in the thick of the English folk revival of the 60’s.

How does this relate at all to McLaughlin, you might ask? Well, Harper is an almost obsessive researcher, and the simple answer is that Jansch and McLaughlin both kind of started as young, rank amateurs on the London scene of the early 60’s. Their paths surely crossed, as both were also session players in London in the early 60’s; Jansch not so much as McLaughlin, but he did record with Donovan as well as some other English artists. But what I’m finding fascinating about the book (I’m only into the 2nd chapter) is Harper’s tracing of the lineage of the folk scene, which has connections across the pond to the United States, and, of course, is responsible for a lot of pollination of the English pop scene.

The English fascination with blues, evidently, really started with Big Bill Broonzy, who played several gigs in the British Isles. The English blues scene is generally said to have been started by Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner; although I’ve known about them for years, this book provides a real timeline and framework for their lives. Davies, who is generally acknowledged as the first English blues harmonica player, was born in 1932, and died, tragically young, in 1964, before he was able to see the enormous influence on rock music that he had. Korner, born in 1928, was a guitarist who did live to see his musical “children” grow up to conquer the pop music scene; his band Blues Incorporated nurtured young performers kind of like Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers did in the jazz field: musicians like Charlie Watts, Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Long John Baldry, Graham Bond, Danny Thompson, Dick Heckstall-Smith, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Geoff Bradford, Rod Stewart, John Mayall, Jimmy Page, Lol Coxhill, Dick Morrissey, John Surman and Mike Zwerin all passed through.

The English music scene was smaller, of course, than the American scene; it was, after all, mostly centered around London. Before the blues revival, but related to it because Broonzy was presented in concert as an American singer of folk songs, what was called the English Folk Revival really had its roots in the post-World War I years. Soho in London became a kind of Bohemian center, drawing people like Dylan Thomas. Post World War II musicologists like Ewan MacColl, A.L. Lloyd, Martin Carthy and The Watersons, among many others, started a movement, sometimes as a reaction against the incursions of American music and sometimes not, to discover and preserve the traditional musics of the Isles. (Similar movements were a’bornin’ in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dublin and Belfast.) There was a healthy diplomatic connection between America and the U.K., though; American folklorist Alan Lomax spent time in London along with Pete Seeger’s half-sister Peggy, who married Ewan MacColl.

Another thing that I found interesting was the influence of Communism in England’s folk scene; I think England is much more politicized than we are, and many of that first generation of English folk musicians were unabashedly Communist. In America, of course, The Weavers had their careers destroyed by the McCarthy pogroms, and seminal New York folk musician Dave Van Ronk, in his excellent autobiography The Mayor of MacDougal Street recalls how leftist politics were part of the DNA of the Greenwich Village folk movement.

scene; I think England is much more politicized than we are, and many of that first generation of English folk musicians were unabashedly Communist. In America, of course, The Weavers had their careers destroyed by the McCarthy pogroms, and seminal New York folk musician Dave Van Ronk, in his excellent autobiography The Mayor of MacDougal Street recalls how leftist politics were part of the DNA of the Greenwich Village folk movement.

Broonzy, Leadbelly, Josh White, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee were folk music heroes in England, and American jazz was also very popular, but many of the aspiring English musicians couldn’t quite grasp the harmonic complexity of jazz or the African polyrhythmic subtleties of the blues, so when they learned songs from the afore-mentioned artists they tended to simplify them, both harmonically and rhythmically, and that’s how skiffle music was born (or that’s one theory, at least). Skiffle was enormously popular, and here’s where the matrix starts: Just about every English rock musician of note in the 60’s started out either in a skiffle band (McLaughlin, the various Beatles) or in a blues band (the Rolling Stones, Clapton, et.al).

The genealogies at this point in time all start to cross: Rod Stewart worked with Long John Baldry, who had performed early in his career at concerts that MacColl presented; Davies and Korner were matriculating students in and out of their bands; the influential guitarist Davy Graham was starting to incorporate elements of Indian music into his playing; bandleaders like Graham Bond and Georgie Fame were employing rhythm sections like Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker; John McLaughlin was playing sessions, skiffle and jazz gigs; Ronnie Scott was employing players of all stripes at his famous jazz club; Jimmie Page and John Paul Jones were doing session work; American singer/songwriter Paul Simon was lurking around in London.

One can point at specific songs as results of all of this intermingling. Simon appropriated Martin Carthy’s arrangement of the traditional song “Scarborough Fair” and Davy Graham’s signature solo guitar piece “Angie” and had much more success with them than either of the Brits could ever dream of (and sparking much long-held resentment, although I do think that Graham at least was compensated). The Animals nicked Van Ronk’s arrangement of “House Of The Rising Sun,” which he had evidently in turn borrowed from the American folk-blues singer Eric Von Schmidt. When Jimmie Page started his mega-group Led Zeppelin, one of the songs on their debut album, “Black Mountain Side,” was a blatant copy of Jansch’s “Blackwater Side,” which in turn was a hybrid of original writer Annie Briggs’ version and a version by future Pentangle mate John Renbourn. (To his karmic credit, Jansch always seemed relatively unfazed by Page’s theft, saying “When you sell your music, you sell your soul. I prefer to share mine.”)

A second wave of English folkies would electrify the music, bands like Fairport Convention, Lindisfarne and Steeleye Span, partially as a reaction against the English blues players and in recognition of the accomplishments in America of The Band. Many of the English musicians respected The Band’s attempt to get back to the roots of Americana, and felt that the traditions of the English Isles had plenty to offer. Another thing that I’m finding interesting is that many of the earliest figures in the English scene were very much children of the period BETWEEN World Wars I and II, which puts a very different spin on the way that they processed the world around them. I think this accounts for the high incidence of Communism.

On the other hand, the earliest figures of the pop scene were very much children of World War II, an experience that we in America can scarcely imagine; if they grew up in London they grew up in a city that was under attack by the Luftwaffe, and following the war they experienced years of forced austerity, as opposed to America, whose economy was stronger than it had ever been. Jansch talks about having to attempt to build his own first guitar, since there was no way he could ever afford to buy one. Some of the earliest skiffle bands consisted of more-or-less homemade instruments. Many of the folk pioneers tell of gigs that literally paid nothing; at least when Bob Dylan played what were called the Basket joints in Greenwich Village he might go home with 4 or 5 bucks in tips, and in one of his early taking blues songs he recalls that his first paid gig in New York was as a harmonica player for a dollar a day. This period of English austerity might partially explain the rock star excesses of the 70’s.

The book is, as I say, obsessively researched, and it might not be your cuppa;, but since I already know and love a lot of this music and many of these musicians I’m really enjoying it. If you’re a Zeppelin or Richard Thompson or Cream or Traffic fan, there’s a lot of deep information here that might interest you. Thanks, Dave!

Steve Hashimoto

This post is reprinted from News From The Trenches, a weekly newsletter of commentary from the viewpoint of a working musician published by Chicago bassist Steve Hashimoto. If you’d like to start receiving it, just let him know by emailing him at steven.hashimoto@sbcglobal.net.