Last week I said that I was tired of writing about dead people, and Lord, I still am, but this one’s kind of personal.

Last week I said that I was tired of writing about dead people, and Lord, I still am, but this one’s kind of personal.

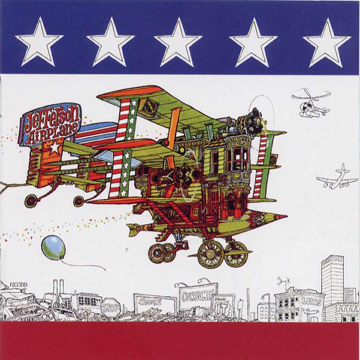

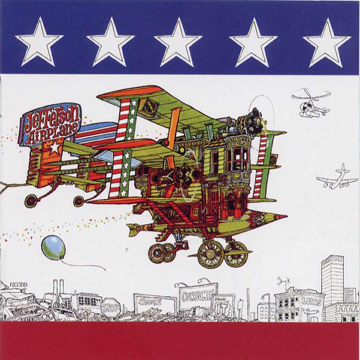

With all due respect to Glenn Frey and Mic Gillette, both of whom were fine musicians whose work I greatly loved, when I heard about the death of Paul Kantner Thursday night I felt something more than the tug of nostalgia. Kantner was the leader of the 60’s San Francisco band Jefferson Airplane, a band that provided the soundtrack to some of the formative years of my life (singer Marty Balin started the band, but Kantner evolved, or some say bullied his way, into the leadership role). The band went through many changes, including several name changes, but for me the classic lineup included Kantner on guitar and vocals, Balin on vocals, Grace Slick on vocals and occasional keyboard, guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, bassist Jack Casady and drummer Spencer Dryden. Kantner was probably the weakest member of the group; Balin and Slick were strong singers with remarkable instruments, Kaukonen was (and is) a good guitarist with strong roots in country blues, Casady remains my favorite bass player of all time, and Dryden brought a certain jazz sensibility to the band. Kantner was not a great guitar player, and his voice had a quality that, as they say, took some getting used to. Many of the songs that he wrote for the band were not the band’s best, and many of them have not aged well.

But that’s precisely why he was so important to the band, I think. He was the political conscience of the band, and he wrote about things he felt strongly about, whether anyone liked it or not. My favorite songs from their recordings tend not to be Paul’s tunes – they actually ranged pretty far for a band of that era, when bands took it as a point of pride to write their own material. They covered songs by David Crosby, the enigmatic Fred Neill, Judy Henske (actually, a song that she sang a lot, ”High Flying Bird,” by Billy Edd Wheeler) and traditional folk and blues tunes. Kantner was generous about sharing writing duties on their records with all of the other band members – none of that “Okay, George and Ringo get one tune each!” business. To my knowledge he never took a guitar solo, and he only occasionally sang lead. He had a unique ear for harmony as a singer; the chief difference between the Airplane’s harmony singing and everyone else’s (Crosby, Stills and Nash, The Beach Boys, The Band, The Eagles) was that they based much of their part-singing on quartal rather than diatonic harmony (a trait they shared with the Engish band Pentangle). Kantner seemed to gravitate towards harmony lines that created a feeling of suspension and ambiguity.

They were simultaneously a product of the time (the hippie 60’s) and creators of the zeitgeist. Whether this was a conscious effort on Kantner’s part or just the way that things happened, the band behaved much like a jazz band, in that musicians were always sitting in and guesting on their records and gigs; the Airplane famously lived in a communal house at 2400 Fulton in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, and I think he also saw the band as a communal family. Kantner himself often alluded to his Teutonic tendency towards control, but I’d have to say that during those early years he didn’t seem like a guy who felt like he had to protect his turf.

He co-wrote the version of ”Wooden Ships,” with David Crosby and Stephen Stills, that appears on the JA album ”Volunteers,” and I think it’s superior to the version on CSN’s debut album. Of course CSN’s version is gorgeous and the playing is competent, but the Airplane’s version has some rough edges, especially in Kantner’s vocal verses, that humanizes it, and it has a wider story arc and a more interesting dynamic.

In 1971, with the Airplane in the throes of dissolution, Kantner released a curious “solo” album called ”Blows Against The Empire,” credited to Jefferson Starship. Later on the Airplane would be officially called the Jefferson Starship, but that was really a different band than this one, and the spin-off band, called Starship, was another completely different animal. The Blows Against The Empire band was an ad-hoc bunch of San Francisco players, including members of The Grateful Dead, Crosby Stills and Nash and Santana (many of whom would also make the unjustly obscure David Crosby solo album ”If I Could Only Remember My Name”). The theme of the album was one of Kantner’s personal obsessions, a science-fiction conceit of leaving Earth and colonizing other planets; he and Slick (Crosby’s hilarious nickname for the couple was Baron Von Tollbooth and the Chrome Nun) had just had a daughter, China, and I guess he really didn’t like the school district. The album’s kind of a mess, but I also find it charming that Kantner could talk his record company into it.

Kantner died from complications from a heart attack, He was 74 years old.

|

In honor of Kantner’s memory, this week’s pick is ”The Ballad Of You And Me And Pooneil,” by The Jefferson Airplane. The song was written by Kantner, who plays guitar and shares lead vocals with Grace Slick and Marty Balin. This is a live version, featuring a pretty cool solo by bassist Jack Casady; guitarist Jorma Kaukonen and drummer Spencer Dryden round out the classic lineup. For a sonically better version check out the original recording on their 1967 album ”After Bathing At Baxter’s.”

This song kind of typifies for me the things that I loved (and that many people hated) about this band, the three-part vocals, the wild and wooly solos, the opaque, surrealistic lyrics. Yes, Grace often sings flat, but I tend to blame the monitor situations (and maybe the acid). And Kantner’s voice is an acquired taste, but he fills a nice little sonic niche between Balin and Slick. In this video (which I have never seen before) it’s obvious that Balin and Slick are like fire and ice at the heart of the band, contributing different kinds of soulfulness. Kantner is the architect and the intellect, staying out of the spotlight but definitely the man behind the curtain. Kaukonen is the flash and Dryden is the glue, but it’s obvious that Casady is the throbbing engine that drives the band.

You can view the video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lHmiFHzPqbM |

This post is reprinted from News From The Trenches, a weekly newsletter of commentary from the viewpoint of a working musician published by Chicago bassist Steve Hashimoto. If you’d like to start receiving it, just let him know by emailing him at steven.hashimoto@sbcglobal.net.

Tags: "The Ballad of You & Me & Pooneil", Jefferson Starship, News From the Trenches, Paul Kantner, Steve Hashimoto

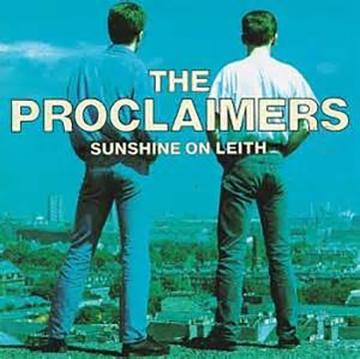

This week’s pick has a little bit of a backstory – it’s the song “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” by the band The Proclaimers. It’s from their 1988 album “Sunshine On Leith.” The Proclaimers are the brothers Charlie and Craig Reid (Charlie on guitar and vocals and Craig on vocals); the band on that album included Jerry Donahue, acoustic and electric guitars; Gerry Hogan, steel guitar; Steve Shaw, fiddle; Stuart Nisbet, pennywhistle and mandolin; Dave Whetstone, melodeon; Pete Wingfield, keyboards; Phil Cranham, bass; and Dave Mattacks and Paul Robinson:, drums and percussion.

This week’s pick has a little bit of a backstory – it’s the song “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” by the band The Proclaimers. It’s from their 1988 album “Sunshine On Leith.” The Proclaimers are the brothers Charlie and Craig Reid (Charlie on guitar and vocals and Craig on vocals); the band on that album included Jerry Donahue, acoustic and electric guitars; Gerry Hogan, steel guitar; Steve Shaw, fiddle; Stuart Nisbet, pennywhistle and mandolin; Dave Whetstone, melodeon; Pete Wingfield, keyboards; Phil Cranham, bass; and Dave Mattacks and Paul Robinson:, drums and percussion.

Last week I said that I was tired of writing about dead people, and Lord, I still am, but this one’s kind of personal.

Last week I said that I was tired of writing about dead people, and Lord, I still am, but this one’s kind of personal. This week’s pick is from Brasil, a samba medley of the songs ”Upa Neguinha, O Morro Não Tem Vez (Favela)” and another song that I’m not familiar with, but I bet there are a bunch of you out there that can help out. They’re performed by the great singer Elis Regina and Jair Rodrigues. Upa was written by Edu Lobo and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri, and O Morro by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes. Both songs portray the political scene in Brasil in the 60’s, when it was ruled by a military dictatorship and the gulf between the wealthy and the impoverished was great.

This week’s pick is from Brasil, a samba medley of the songs ”Upa Neguinha, O Morro Não Tem Vez (Favela)” and another song that I’m not familiar with, but I bet there are a bunch of you out there that can help out. They’re performed by the great singer Elis Regina and Jair Rodrigues. Upa was written by Edu Lobo and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri, and O Morro by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes. Both songs portray the political scene in Brasil in the 60’s, when it was ruled by a military dictatorship and the gulf between the wealthy and the impoverished was great.