“Hash’s Faves” generally are musical but this one is literary.

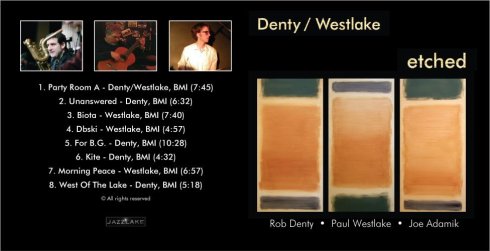

The late Donald E. Westlake is my all-time favorite author. If I can write at all it’s by following his example.

Donald Westlake

Although I don’t recall seeing any specifics in any biographies of him, I’m guessing that he has some sort of musical background, as there are many small but telling tidbits, descriptions of musicians, musician characters, etc., in much of his writing. I also guess that he has some sort of connection to Illinois (I do know that he ghost-wrote a lot of soft-porn potboilers for a publisher in Evanston in the early 60’s) as there are frequent mentions of cities in Illinois. And I’m guessing he has a theatrical background, as many of his main characters are actors.

Within the last weeks I’ve read his penultimate book, Memory, and one of his earliest, The Cutie. It’s been interesting. Just to give some context, Westlake’s earliest works were kind of all over the place – science fiction, hard-boiled detective and crime stuff, and humor. He was prolific, utilizing more than a dozen pseudonyms, and at one point churning out a book every couple of days. One of his most famous inventions was a character named Parker, a nihilistic criminal mastermind – pitiless, brutal, vicious and brilliant. Westlake wrote a series of Parker novels under the name Richard Stark, and over the years they have become cult classics, and have been the inspiration for some movies and graphic novels. But at some point Westlake discovered an undercurrent of wild humor emerging in his writing, almost beyond his control, a voice that didn’t fit Parker’s character at all, so he started a new series of books featuring another criminal mastermind named John Archibald Dortmunder. Dortmunder was far from brutal, and the books are very funny.

Westlake wrote in this humorous vein for many years, and a lot of his funny books were made into movies, with varying degrees of success, but his last couple of books got pretty dark. Memory is about an actor who loses his memory, and is a melancholy exploration of what the “self” is. At one point the protagonist, Paul Cole, visits his first acting teacher in an attempt to fill in some of the gaps in his knowledge of his self. The teacher’s reaction to seeing Cole, in his present confused state, is extremely dark, but I thought this monologue was germane not only to those in the theatrical profession but to any artist:

“Every once in a while,” he called, walking around and around, “through that door over there comes an actor. Every once in a while, every once in a great great while. Not one of these pale idiots who wants to be an actor, can you think of anything more foolish? It’s like wanting to fly, isn’t it, you can or you can’t and that’s an end to it, wanting has nothing to do with it. You can even want not to fly, but if you’ve got the wings you’ll fly, one way or another, and wanting has nothing to do with that.”

He stopped again. He was now very near the door, standing facing it with his hands on his hips in a belligerent way. He talked now at the door, but loudly enough for Cole to hear him, with a slight echo in the words. “These young fools come in here with their feeble desires and chip away at my life! Like woodpeckers. What sort of a useless stupid appendix of the emotions is desire, what has desire ever done for anybody but turn him into an embarrassing fool? How can you want to be an actor? You are or you aren’t, and ninety-nine percent of them coming through the door are not. But then there’s the one who is.”

Kirk’s voice had lowered on the last sentence, so that Cole could barely hear him, and now he turned back and came walking straight toward the platform, looking directly at Cole now as he spoke: “That’s what I live for, Paul, that’s the reason for my existence. I sit here and wait and wait and wait, and every once in a while an actor comes through that door back there, a boy or a girl who’s been an actor from the minute he was born, whether he knew it or not. They come to me, and I give them the rudiments, I give them the terms for what they already know how to do, and I give them freely from my own poor store of contacts in the theatrical world, and I watch them discover themselves, discover their own powers and the gulf that yawns between them and the poor fools sitting around them in class…

Now, I don’t necessarily agree with the bleakness of this assessment, but I do agree with the essence of it, that some people just aren’t cut out to be whatever– musicians, painters, poets, actors, photographers, sculptors or writers. One may desire to be, and I would certainly encourage anyone who has such a desire to pursue it, if only for one’s own fulfillment. But very few people can become Charlie Parkers or Marlon Brandos or Picassos. With hard work and dedication, though, one can become proficient enough as a craftsman to produce work that he (or she) can be proud of, and can work in their chosen field. That, I guess, is what I am. I ain’t Jaco Pastorious or Herb Lubalin or Westlake; I wish I was, but I’m pretty happy with what I’ve got. That doesn’t mean I’m satisfied, by any means, but neither am I ashamed.

As a sidenote, I’ve always been fascinated with the way that Westlake inserts sly little cross-references from previous works into his books, so I was absolutely thrilled to see that he used an address on Grove Street in Greenwich Village in Memory (I read that one first), and an address on Grove Street also pops up in “The Cutie.” Fifty years separated the writing of those books.

The book that introduced me to Westlake, by the way, and that got me hooked is called Dancing Aztecs; it’s not one of his Dortmunder books but it is very funny, and it is a caper book. Lise Dirks turned me on to the book and I will forever be indebted to her.

Steve Hashimoto

This post is reprinted from News From The Trenches, a weekly newsletter of commentary from the viewpoint of a working musician published by Chicago bassist Steve Hashimoto. If you’d like to start receiving it, just let him know by emailing him at steven.hashimoto@sbcglobal.net.

Steve Hashimoto

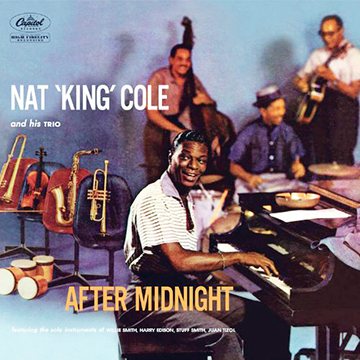

This week’s pick is the jazz standard ”Just You, Just Me,” from Nat “King” Cole’s After Midnight album. The song is by Jesse Greer and Raymond Klages, from a 1929 movie called Marianne. Cole’s album featured his trio, with Cole singing and playing piano, guitarist John Collins and bassist Charlie Harris. On this song, they’re joined by Lee Young, Lester’s brother, on drums, and Willie Smith on alto saxophone.

This week’s pick is the jazz standard ”Just You, Just Me,” from Nat “King” Cole’s After Midnight album. The song is by Jesse Greer and Raymond Klages, from a 1929 movie called Marianne. Cole’s album featured his trio, with Cole singing and playing piano, guitarist John Collins and bassist Charlie Harris. On this song, they’re joined by Lee Young, Lester’s brother, on drums, and Willie Smith on alto saxophone. This week’s pick is a funky love song by Prince, “Forever In My Life.” It’s originally from his 1987 album Sign O’ The Times.The album was a quasi concert film, and featured Prince’s band at the time, Prince on lead vocals and guitar (and, one assumes, drums, keyboards and bass); Wendy Melvoin, guitar, percussion and vocals; Lisa Coleman, keyboards, sitar, flute and vocals; Sheila E, drums, percussion and vocals; Dr. Fink, keyboards; Miko Weaver, guitar; Brown Mark, bass; Bobby Z,drums; Eric Leeds, saxophone; Atlanta Bliss, trumpet; and Sheena Easton, Susannah Melvoin and Jill Jones, vocals. The very different, expanded live version here is from the movie Sign O’ The Times and features a slightly different band, adding keyboardist/vocalist Boni Boyer (in a star turn), bassist Levi Seacer and dancer Cat Glover.

This week’s pick is a funky love song by Prince, “Forever In My Life.” It’s originally from his 1987 album Sign O’ The Times.The album was a quasi concert film, and featured Prince’s band at the time, Prince on lead vocals and guitar (and, one assumes, drums, keyboards and bass); Wendy Melvoin, guitar, percussion and vocals; Lisa Coleman, keyboards, sitar, flute and vocals; Sheila E, drums, percussion and vocals; Dr. Fink, keyboards; Miko Weaver, guitar; Brown Mark, bass; Bobby Z,drums; Eric Leeds, saxophone; Atlanta Bliss, trumpet; and Sheena Easton, Susannah Melvoin and Jill Jones, vocals. The very different, expanded live version here is from the movie Sign O’ The Times and features a slightly different band, adding keyboardist/vocalist Boni Boyer (in a star turn), bassist Levi Seacer and dancer Cat Glover. This week’s pick is one of the tunes that was on that reel-to-reel bootleg that introduced me to jazz; “Seven Come Eleven,” by Charlie Christian, with the Benny Goodman Sextet, Benny on clarinet, Christian on guitar, Lionel Hampton on vibes, Fletcher Henderson on piano, Artie Bernstein on bass and Nick Fatool on drums.

This week’s pick is one of the tunes that was on that reel-to-reel bootleg that introduced me to jazz; “Seven Come Eleven,” by Charlie Christian, with the Benny Goodman Sextet, Benny on clarinet, Christian on guitar, Lionel Hampton on vibes, Fletcher Henderson on piano, Artie Bernstein on bass and Nick Fatool on drums. This week’s pick is some Beatles music, the Lennon/McCartney composition ”Things We Said Today.” It was written and recorded in 1964, originally intended for use in the film A Hard Day’s Night, but didn’t make the cut. It was released on the soundtrack album, though. This was still in the time period when the boys were recording as a self-contained unit, so it’s John Lennon on guitar, piano and vocals; Paul McCartney on bass and lead vocals; George Harrison on guitar and vocals; and Ringo Starr on drums and tambourine.

This week’s pick is some Beatles music, the Lennon/McCartney composition ”Things We Said Today.” It was written and recorded in 1964, originally intended for use in the film A Hard Day’s Night, but didn’t make the cut. It was released on the soundtrack album, though. This was still in the time period when the boys were recording as a self-contained unit, so it’s John Lennon on guitar, piano and vocals; Paul McCartney on bass and lead vocals; George Harrison on guitar and vocals; and Ringo Starr on drums and tambourine.

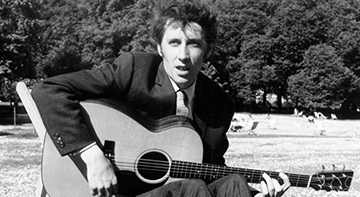

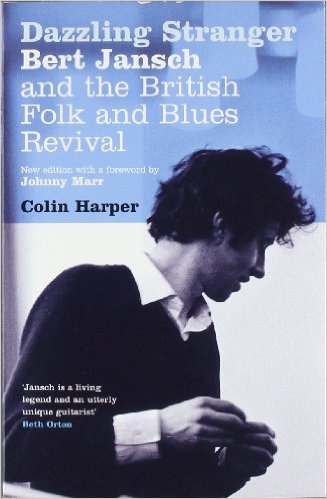

scene; I think England is much more politicized than we are, and many of that first generation of English folk musicians were unabashedly Communist. In America, of course, The Weavers had their careers destroyed by the McCarthy pogroms, and seminal New York folk musician Dave Van Ronk, in his excellent autobiography The Mayor of MacDougal Street recalls how leftist politics were part of the DNA of the Greenwich Village folk movement.

scene; I think England is much more politicized than we are, and many of that first generation of English folk musicians were unabashedly Communist. In America, of course, The Weavers had their careers destroyed by the McCarthy pogroms, and seminal New York folk musician Dave Van Ronk, in his excellent autobiography The Mayor of MacDougal Street recalls how leftist politics were part of the DNA of the Greenwich Village folk movement. This week’s pick has a little bit of a backstory – it’s the song “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” by the band The Proclaimers. It’s from their 1988 album “Sunshine On Leith.” The Proclaimers are the brothers Charlie and Craig Reid (Charlie on guitar and vocals and Craig on vocals); the band on that album included Jerry Donahue, acoustic and electric guitars; Gerry Hogan, steel guitar; Steve Shaw, fiddle; Stuart Nisbet, pennywhistle and mandolin; Dave Whetstone, melodeon; Pete Wingfield, keyboards; Phil Cranham, bass; and Dave Mattacks and Paul Robinson:, drums and percussion.

This week’s pick has a little bit of a backstory – it’s the song “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” by the band The Proclaimers. It’s from their 1988 album “Sunshine On Leith.” The Proclaimers are the brothers Charlie and Craig Reid (Charlie on guitar and vocals and Craig on vocals); the band on that album included Jerry Donahue, acoustic and electric guitars; Gerry Hogan, steel guitar; Steve Shaw, fiddle; Stuart Nisbet, pennywhistle and mandolin; Dave Whetstone, melodeon; Pete Wingfield, keyboards; Phil Cranham, bass; and Dave Mattacks and Paul Robinson:, drums and percussion. Last week I said that I was tired of writing about dead people, and Lord, I still am, but this one’s kind of personal.

Last week I said that I was tired of writing about dead people, and Lord, I still am, but this one’s kind of personal. This week’s pick is from Brasil, a samba medley of the songs ”Upa Neguinha, O Morro Não Tem Vez (Favela)” and another song that I’m not familiar with, but I bet there are a bunch of you out there that can help out. They’re performed by the great singer Elis Regina and Jair Rodrigues. Upa was written by Edu Lobo and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri, and O Morro by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes. Both songs portray the political scene in Brasil in the 60’s, when it was ruled by a military dictatorship and the gulf between the wealthy and the impoverished was great.

This week’s pick is from Brasil, a samba medley of the songs ”Upa Neguinha, O Morro Não Tem Vez (Favela)” and another song that I’m not familiar with, but I bet there are a bunch of you out there that can help out. They’re performed by the great singer Elis Regina and Jair Rodrigues. Upa was written by Edu Lobo and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri, and O Morro by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes. Both songs portray the political scene in Brasil in the 60’s, when it was ruled by a military dictatorship and the gulf between the wealthy and the impoverished was great.